The Ultimate Guide to Eventual Consistency in Distributed Systems

You hit ‘Post’ on your latest generative AI creation. It appears on your profile instantly. But behind the scenes, a fascinating process begins—a carefully choreographed dance to share your update with followers across the globe without bringing the entire system to its knees. How is this possible?

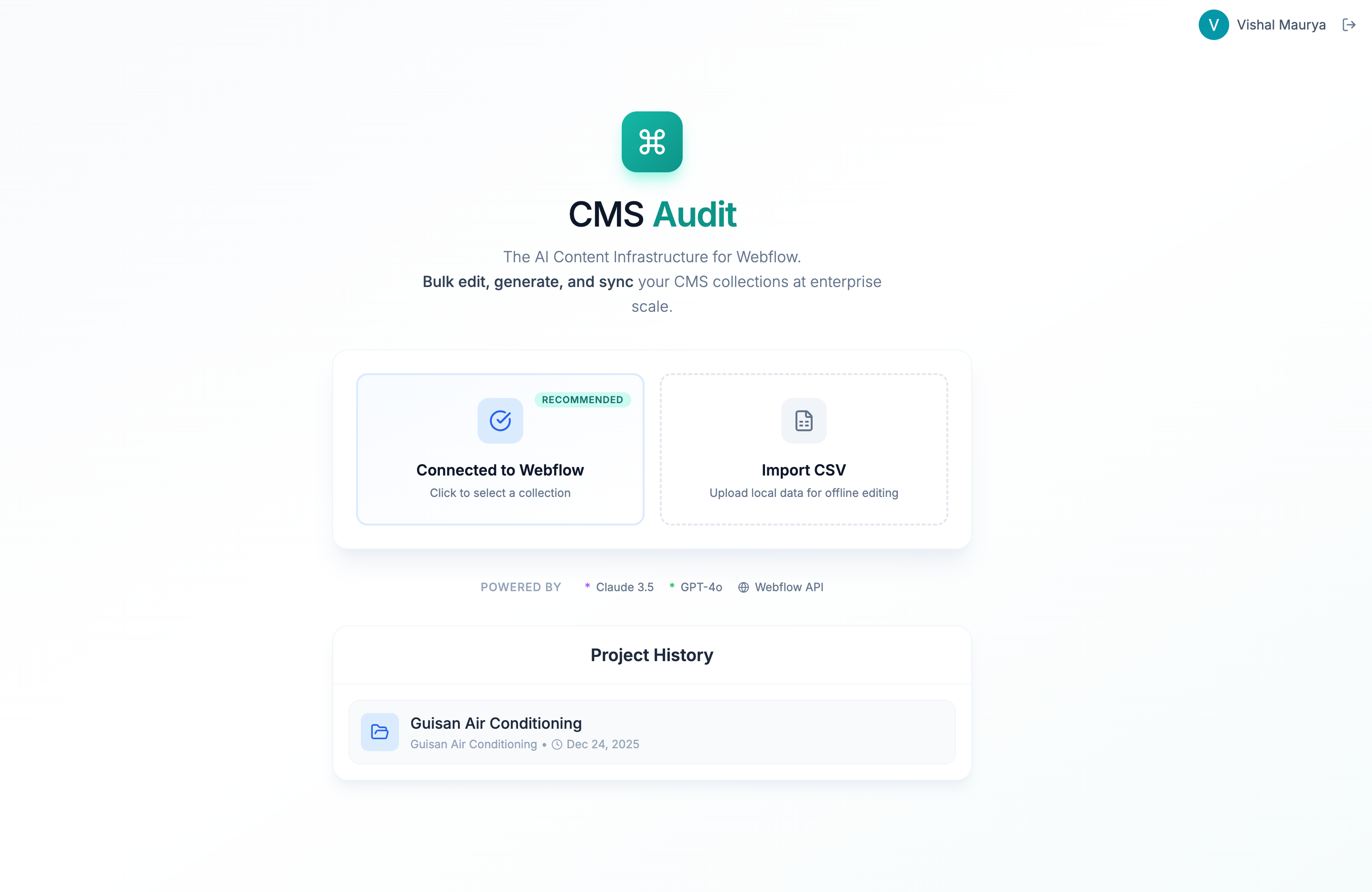

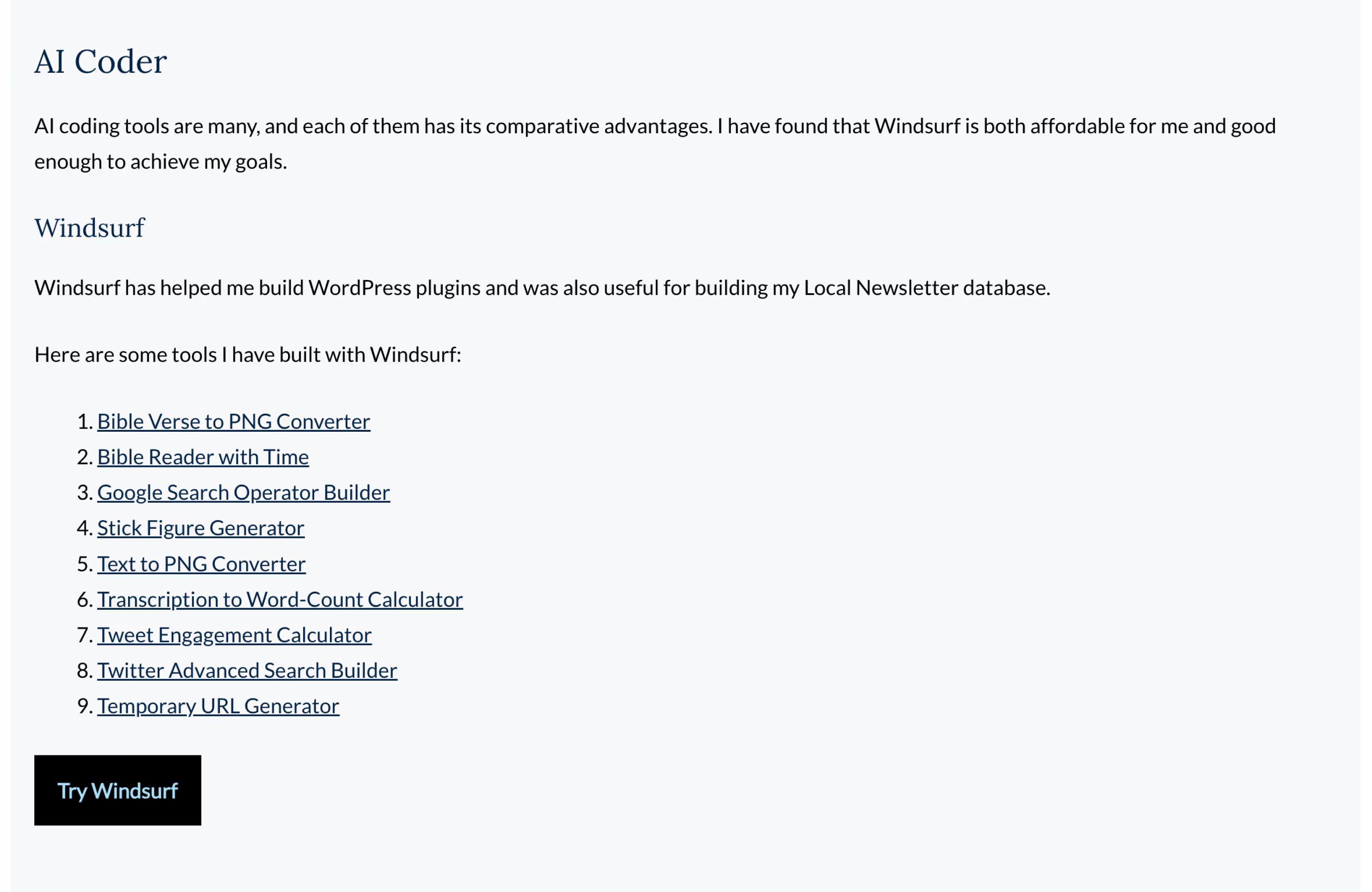

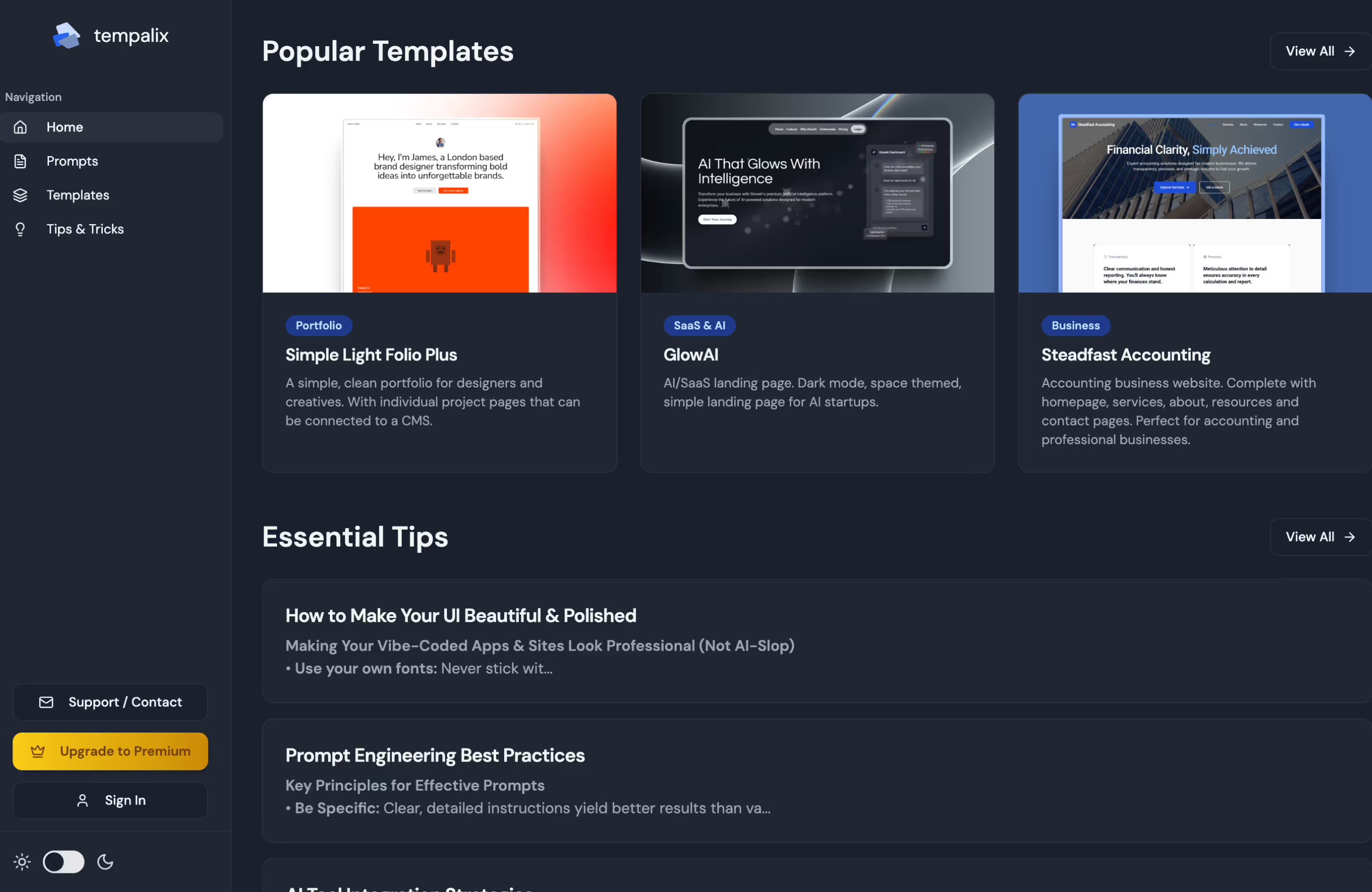

The answer lies in a powerful architectural choice: embracing a little bit of temporary chaos to achieve massive scale. This is the world of eventual consistency, a concept that powers the most resilient and high-performance applications we use every day, from social media feeds to the very [] that inspire developers. If you've ever wondered how platforms handle millions of concurrent users gracefully, you're about to discover one of their most important secrets.

The Scalability Dilemma: Why You Can't Have It All

In a perfect world, every user would see the exact same data at the exact same time. This is called strong consistency. Imagine a single, shared ledger book; when one person writes in it, everyone else sees the update immediately. It’s simple and predictable.

But what happens when you have millions of users and your database is distributed across servers in New York, Tokyo, and Frankfurt? Insisting that every server agrees on the latest update before anyone can proceed creates a massive bottleneck. The Tokyo server has to wait for confirmation from New York and Frankfurt before it can show a user a new 'like' on a photo. This delay, or latency, is the enemy of a good user experience.

This challenge is formalized by the CAP Theorem, a fundamental principle in distributed systems. It states that a distributed database can only provide two of the following three guarantees at any given time:

- Consistency (C): Every read receives the most recent write or an error.

- Availability (A): Every request receives a (non-error) response, without the guarantee that it contains the most recent write.

- Partition Tolerance (P): The system continues to operate despite network failures that split the system into multiple groups (partitions).

Since network failures are a fact of life, Partition Tolerance (P) is non-negotiable. This means you are forced to make a strategic trade-off between Consistency (C) and Availability (A).

A visual representation of the CAP Theorem, showing a choice between Consistency and Availability when Partition Tolerance is a given.

This is where eventual consistency comes in. By relaxing the demand for immediate, universal agreement, we choose Availability and Partition Tolerance. We accept that for a short period, different users might see slightly different data. The system guarantees that eventually, all replicas will converge to the same state.

This philosophy is often summarized as BASE:

- Basically Available: The system prioritizes availability.

- Soft state: The state of the system may change over time, even without input.

- Eventually consistent: The system will become consistent over time, once the system stops receiving input.

It’s not a "weaker" model; it's a deliberate engineering trade-off for building incredibly fast and resilient [] at a global scale.

The Architect's Toolbox: Patterns for Eventual Consistency

Choosing eventual consistency is just the first step. Implementing it requires specific architectural patterns that manage the flow of data and handle potential issues gracefully. Here are the most common patterns you'll encounter.

Event-Driven Architecture: The Ripple Effect

This decouples your services. The initial photo upload is incredibly fast because it only has to do one thing: announce that the event happened. The rest of the work happens asynchronously in the background.

Use Case: A social media platform. When you post, the event is published. Your timeline updates instantly for you ("read-your-writes"), while your followers' feeds update asynchronously as the event propagates through the system.

Architect's Pitfall: Without proper monitoring, it can be difficult to trace the journey of an event through the system. If a downstream service fails, you need a strategy (like a dead-letter queue) to handle unprocessed events.

The Saga Pattern: Choreographing Distributed Actions

What about complex operations that involve multiple services, like booking a vacation? You need to book a flight, reserve a hotel, and rent a car. In a traditional database, you’d wrap this in a single transaction—if one part fails, everything rolls back.

In a distributed system, you can’t lock resources across different services. The Saga pattern solves this by sequencing local transactions. Each step of the process publishes an event that triggers the next. If any step fails, the saga executes compensating transactions to undo the preceding steps. For example, if the car rental fails, compensating transactions are triggered to cancel the hotel and flight bookings.

Use Case: An e-commerce order. The "Order Placed" saga might involve:

- Reserving inventory (Inventory Service).

- Processing payment (Payment Service).

- Scheduling shipping (Shipping Service).

If the payment fails, a compensating transaction is triggered to release the inventory.

CQRS: Two Paths for Your Data

CQRS stands for Command Query Responsibility Segregation. It’s a fancy way of saying you should use different models for updating data (Commands) and reading data (Queries).

Often, your application reads data far more often than it writes it. CQRS allows you to optimize these paths separately. You can have a write database designed for fast, simple inserts, and one or more read databases that are highly optimized for the complex queries needed to display data to users. Data is synchronized from the write model to the read models eventually.

A flow diagram illustrating CQRS. A "Command" goes to the Write Model, which updates a database. An event then triggers an update to a separate, optimized Read Model, which serves all "Queries."

Use Case: A blog platform. The "write" side is simple: save a post. The "read" side is complex: show posts by author, by tag, by date, with comment counts, etc. CQRS allows you to create highly optimized read tables or views for each of these scenarios, which are updated in the background whenever a post is created or edited.

Handling the Inevitable: Advanced Conflict Resolution

A common fear with eventual consistency is, "What happens if two people update the same thing at the same time?" This is known as a write conflict.

The simplest strategy is "last-write-wins," where the latest timestamped update is the one that's kept. But this can lead to lost data. Imagine two people editing a shared document; you wouldn't want one person's paragraph to completely overwrite the other's.

For more complex scenarios, developers use smarter techniques:

- Vector Clocks: A mechanism that helps a system determine the causal relationship between events without relying on synchronized clocks. It can detect if one version precedes another or if they are in conflict, allowing for more intelligent merging.

- Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs): These are special data structures designed to be replicated across multiple computers. They have a fascinating mathematical property: they can be updated independently and concurrently without coordination, and they are guaranteed to eventually converge in a way that resolves conflicts automatically. A simple example is a counter (like a 'like' button) where increment operations from different servers can be applied in any order and still result in the correct final sum.

Is Eventual Consistency Right for You? A Decision Framework

Eventual consistency is a powerful tool, but it's not a silver bullet. Use this checklist to decide if it fits your use case:

- Can the business tolerate temporary data staleness?

- Yes: A 'like' count being a few seconds out of date is fine. -> Good candidate.

- No: A bank account balance must be perfectly accurate. -> Use strong consistency.

- Is high availability a critical requirement?

- Yes: The system must remain online and responsive even if parts of it fail. -> Good candidate.

- No: It's acceptable for the system to be briefly unavailable during network issues. -> Strong consistency might be simpler.

- Is your system distributed across multiple services or geographic locations?

- Yes: You are already dealing with network latency and partitions. -> Good candidate.

- No: You are running a single-server monolith. -> Strong consistency is often the default and easier to manage.

- Are your read and write patterns significantly different?

- Yes: You have a high volume of reads and a lower volume of writes. -> A pattern like CQRS is a great fit.

- No: Your read/write ratio is balanced. -> The benefits might be less pronounced.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is eventual consistency in simple terms?It's a model where you accept that updates to your data won't be visible everywhere instantly. The system guarantees that if no new updates are made, all copies of the data will eventually become consistent.

2. What's the main difference between eventual and strong consistency?Strong consistency guarantees that a read will always return the most recent write, making the system act like a single machine. Eventual consistency prioritizes availability, allowing reads to sometimes return slightly older data while updates are propagating.

3. Why would anyone ever choose eventual consistency?For performance, scalability, and resilience. Systems that require strong consistency can become slow and unavailable during network partitions. Eventual consistency allows systems to stay fast and responsive, which is crucial for the kinds of [] that are being built today.

Your Journey into Resilient Architecture

Understanding eventual consistency is no longer an esoteric niche; it's a core competency for anyone building modern, high-scale applications. By trading a small amount of immediacy for immense gains in availability and performance, you unlock the ability to create systems that can delight users at a global scale.

The next time you explore the inspiring [] on our platform, consider the invisible architecture that makes them possible. Many of them rely on these very principles to deliver fast, creative, and resilient experiences.

.svg)